Click here to return to the main page.

[A former New York Times reporter who covered the rescue operations in the hours after the November 22, 1950 Long Island Railroad crash recalls the events of that night.]

Recollections

By WALTER H. STERN

It was the night before Thanksgiving, 1950. I had just finished my day's work as a reporter for The New York Times and was about to have dinner with my parents in the Beverly House Apartments in Kew Gardens, part of which faces the Long Island Rail Road tracks east of Lefferts Boulevard. Suddenly, I heard the sirens of many emergency vehicles and could not resist looking out the dining room window. I saw countless red flashing signal lights and a train at what appeared to be at a standstill. Some months earlier, I had covered a Long Island Rail Road train wreck at Rockville Centre, NY in which 31 people were killed. Instinctively, I knew I was about to cover another train accident.

I left The Beverly House through the rear entrance and was able to get access to the tracks nearby on Cuthbert Road about half a block west of 124th Road. When I realized the magnitude of the disaster, I returned to Cuthbert Road, rang the doorbell of a house nearby, and asked to use their telephone to advise the Times. There were no cell phones in those days. The night City Editor was incredulous and decided to send another reporter to the scene just in case I had lost hold of my senses. My estimate of the toll was beyond their belief. In turn, I told them to send anybody available on the night staff to Queens General and Mary Immaculate Hospitals because that is where any survivors were being taken. I thought possibly some of them could be interviewed.

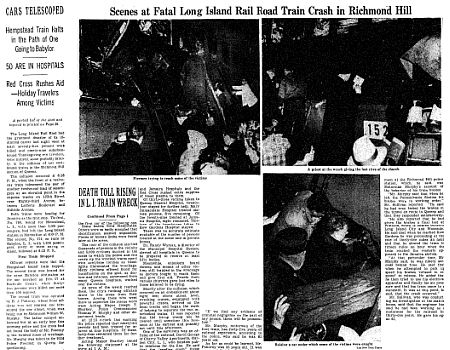

Returning to the tracks, the first living person I encountered was a U.N. correspondent for a British newspaper. Together we walked the length of the two trains involved. At first we heard no sounds from within the impacted cars. However, after a few minutes, perhaps because their initial shock and trauma had begun to subside, we began to hear cries for help coming from those still alive inside. As we surveyed the corpses staring out of windows or, in some cases, hanging out of them, the British journalist made his unforgettable comment, "I say, this is a bad one." It seems he was riding in the last car of the second (Babylon) train -- the one which collided with the rear of the stationary first train bound for Hempstead. He had felt little more than a jolt, and so was able to climb off and join me.

The more we looked closely at each car near the point of collision, the more evident it became that this was a far worse accident than the one in Rockville Centre the previous February. Before long, other reporters arrived -- one from the Times, and those from other papers as well as Associated Press, United Press and International News Service. Together, we tried to interview survivors who seemed well enough to talk and were not taken to hospitals. All of them told essentially the same story -- a routine trip home and a sudden jolt, the sounds of crunching metal, the screams and wails of the dying.

Together we walked to the point of impact, i.e., the last car of the first (Hempstead) train and the first car of the second (Babylon) train. The body of the Babylon train's motorman was hardly identifiable as human. In the last car of the Hempstead train, we also found bodies mangled beyond recognition.

Questions to the police about what they had determined met with icy stares. They were still trying to put the pieces together, though we all acknowledged that a meaningful investigation was days and possibly weeks off.

The owners of the house where I had first used the telephone were very accommodating, giving me a chance to phone in my report to a rewrite man. Questions and more questions, but most were unanswerable under the circumstances. Meanwhile, the rewrite man interrupted me to take a call from a reporter at one of the hospitals. There was little more for me to do. The rest of the story would have to come from other sources -- officials had become involved and it was late enough for closing out the last edition of the Times in any event.

I returned around 3 A.M. to my parents' apartment and was in for a bit of a shock. All night I had watched police and others carry away the dead in body bags. Now I saw what I believed at first to be body bags on our foyer floor. It turned out they were bags containing chairs my parents had ordered for their Thanksgiving party.

Months later, when the gravity of the accident had worn off, I, like most newsmen, began to make silly jokes about that night. I did so to a friend of mine who did not speak to me again for years. It seems his wife's father was killed in the wreck.

Click here to return to the main page.